DocumentRoot /var/www/html

Chapter 2: URL Mapping

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the various ways that the Apache http server handles URL Mapping.

When the Apache http server receives a request, it is processed in a variety of ways to see what resource it represents. This process is called URL Mapping.

mod_rewrite is part of this process, but will be handled separately, since it is a large portion of the contents of this book.

The exact order in which these steps are applied may vary from one configuration to another, so it is important to understand not only the steps, but the way in which you have configured your particular server.

mod_rewrite

mod_rewrite is perhaps the most powerful part of this process. That is, of course, why it features prominently in the name of this book. Indeed, mod_rewrite spans several chapters of this book, and has an entire Part all its own, part mod_rewrite.

For now, we’ll just say that mod_rewrite fills a variety of different roles in the URL mapping process. It can, among other things, modify a URL once it is received, in many different ways.

While this usually happens before the other parts of URL mapping, in certain circumstances, it can also perform that rewriting later on in the process.

This, and much more, will be revealed in the coming chapters.

DocumentRoot

The DocumentRoot directive specifies the filesystem directory from which static content will be served. It’s helpful to think of this as the default behavior of the Apache http server when no other content source is found.

Consider a configuration of the following:

With that setting in place, a request for http://example.com/one/two/three.html will result in the file /var/www/html/one/two/three.html being served to the client with a MIME type derived from the file name - in this case, text/html.

The DirectoryIndex directive specifies what file, or files, will be served in the event that a directory is requested. For example, if you have the configuration:

DocumentRoot /var/www/html DirectoryIndex index.html index.php

Then when the URL http://example.com/one/two/ is requested, Apache httpd will attempt to serve the file /var/www/html/index.html and, if it’s not able to find that, will attempt to serve the file /var/www/html/index.php.

If neither of those files is available, the next thing it will try to do is serve a directory index.

Automatic directory listings

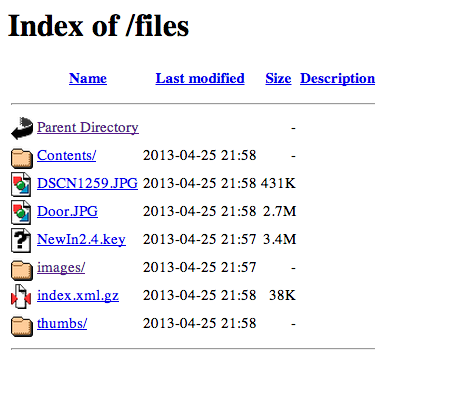

The module mod_autoindex serves a file listing for any directory that doesn’t contain a DirectoryIndex file. (See DirectoryIndex <directoryindex>.)

To permit directory listings, you must enable the Indexes setting of the Options directive:

Options +Indexes

See the documentation of the Options http://httpd.apache.org/docs/current/mod/core.html#options for further discussion of that directive.

If the Indexes option is on, then a directory listing will be displayed, with whatever features are enabled by the IndexOptions directive.

Typically, a directory will look like the example shown below.

For further discussion of the autoindex functionality, consult the mod_autoindex documentation at http://httpd.apache.org/docs/current/mod/mod_autoindex.html.

Future versions of this book will include more detailed information about directory listings.

Alias

The Alias directive is used to map a URL to a directory path outside of your DocumentRoot directory.

Alias /icons /var/www/icons

An Alias is usually accompanied by a <Directory> stanza granting httpd permission to look in that directory. In the case of the above Alias, for example, add the following:

<Directory /var/www/icons> Require all granted </Directory>

Or, if you’re using httpd 2.2 or earlier:

<Directory /var/www/icons> Order allow,deny Allow from all </Directory>

There’s a special form of the Alias directive - ScriptAlias - which has the additional property that any file found in the referenced directory will be assumed to be a CGI program, and httpd will attempt to execute it and sent the output to the client.

CGI programming is outside of the scope of this book. You may read more about it at http://httpd.apache.org/docs/current/howto/cgi.html

Redirect

The purpose of the Redirect directive is to cause a requested URL to result in a redirection to a different resource, either on the same website or on a different server entirely.

The Redirect directive results in a Location header, and a 30x status code, being sent to the client, which will then make a new request for the specified resource.

The exact value of the 30x status code will influence what the client does with this information, as indicated in the table below:

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

300 |

Multiple Choice - Several options are available |

301 |

Moved Permanently |

302 |

Temporary Redirect |

304 |

Not Modified - use whatever version you have cached |

Other 30x statuses are available, but these are the only ones we’ll concern ourselves with at the moment.

The syntax of the Redirect directive is as follows:

Redirect [status] RequestedURL TargetUrl

Location

The <Location> directive limits the scope of the enclosed directives by URL. It is similar to the <Directory> directive, and starts a subsection which is terminated with a </Location> directive. <Location> sections are processed in the order they appear in the configuration file, after the <Directory> sections and .htaccess files are read, and after the <Files> sections.

<Location> sections operate completely outside the filesystem. This has several consequences. Most importantly, <Location> directives should not be used to control access to filesystem locations. Since several different URLs may map to the same filesystem location, such access controls may by circumvented.

The enclosed directives will be applied to the request if the path component of the URL meets any of the following criteria:

The specified location matches exactly the path component of the URL. The specified location, which ends in a forward slash, is a prefix of the path component of the URL (treated as a context root). The specified location, with the addition of a trailing slash, is a prefix of the path component of the URL (also treated as a context root). In the example below, where no trailing slash is used, requests to /private1, /private1/ and /private1/file.txt will have the enclosed directives applied, but /private1other would not.

<Location /private1>

# ...

</Location>

In the example below, where a trailing slash is used, requests to /private2/ and /private2/file.txt will have the enclosed directives applied, but /private2 and /private2other would not.

<Location /private2/>

# ...

</Location>

When to use <Location> Use <Location> to apply directives to content that lives outside the filesystem. For content that lives in the filesystem, use <Directory> and <Files>. An exception is <Location />, which is an easy way to apply a configuration to the entire server. For all origin (non-proxy) requests, the URL to be matched is a URL-path of the form /path/. No scheme, hostname, port, or query string may be included. For proxy requests, the URL to be matched is of the form scheme://servername/path, and you must include the prefix.

The URL may use wildcards. In a wild-card string, ? matches any single

character, and * matches any sequences of characters. Neither wildcard

character matches a / in the URL-path.

Regular expressions can also be used, with the addition of the ~ character. For example:

<Location ~ "/(extra|special)/data">

#...

</Location>

would match URLs that contained the substring /extra/data or /special/data. The directive <LocationMatch> behaves identically to the regex version of <Location>, and is preferred, for the simple reason that ~ is hard to distinguish from - in many fonts, leading to configuration errors when you’re following examples.

<LocationMatch "/(extra|special)/data">

#...

+

</LocationMatch>

The <Location> functionality is especially useful when combined with the SetHandler directive. For example, to enable status requests, but allow them only from browsers at example.com, you might use:

<Location /status> SetHandler server-status Require host example.com </Location>

Virtual Hosts

Rather than running a separate physical server, or separate instance of httpd, for each website, it is common practice run sites via virtual hosts. Virtual hosting refers to running more than one web site on the same web server.

Virtual hosts can be name-based - that is, multiple hostnames resolving to the same IP address - or IP based - that is, a dedicated IP address for each site - depending on various factors including availability of IP addresses and preference. Name-based virtual hosting is more common, but there are scenarios in which IP-based hosting may be preferred.

Proxying

TODO

mod_actions

TODO

mod_imagemap

TODO

mod_negotiation

TODO

File not found

In the event that a requested resource is not available, after all of the above mentioned methods are attempted to find it …

TODO